Project description : one woman play 1995

My 10th Calabash

– voices from an African village

– voices from an African village

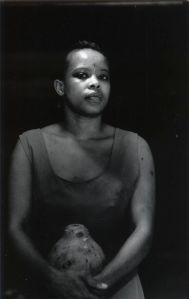

A letter to a friend: “My 10th Calabash” became in some ways a puppet play. The puppets were an assembly of dried gourds that gradually became a glowing heap of clues into the social organisation of an African village. The puppeteer swung and hollered and chastised, perhaps unaware that she was fully visible, but at any rate oblivious to the fact that ‘you don’t do such things’.

The project was to summon up the village where my old co-conspirator Chiku Ali spent the first 14 years of her life: a cluster of mud huts at the edge of the Tanzanian jungle.

Our angle was to follow her memory as I, the essential social-anthropologist, tried to piece together the cultural attributes and family lineages of her Nyaturu people. Almost by coincidence, there were calabashes at each juncture. Calabash for brewing millet beer, preserving salt, ritual slaughter, milk, porridge, the Rites of Passage; between them: admonition, the facts of life and a parade of the women by the well.

Of course, it is the size of these women that carries the evening; women reared on bride price and polygamy, women whose fisticuffs are as fierce as your local wharf’s, and whose social training includes the mocking and berating of every passing uncle. That the actress is clearly cut of the same cloth, merely adds to the danger of the meeting.

By the end of the piece, no coherent social-anthropological theory could be proffered; the flood of detail, both significant and not, remained a subjective pile of field-notes. What had occurred however was the actress’s voyage to the place of her very persuasive power. She was generous but never subservient. If we had listened carefully, we could recognise that our compelling new acquaintances lived deep in the doubly stricken drought and AIDS belt. The village’s days may be numbered, but that’s not the story the calabash tell.

——

The other thematic component of the piece is its broken Norwegian; the actor’s struggle to survive a grammatical constellation that crumbles at each preposition. And so kudos to the writer who squeezes an evocative poetry out of linguistic banality. Our daily frustration becomes our militancy – as the tangible joy of breaking the sound-barrier puts all native speakers to shame.

We promise ourselves a good long life for the piece. Chiku is central in the work of the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices (read female genital mutilation) and is off to Beijing ( UN’s International Congress of Women) to sit on a panel or two. The calabash are light and flexible so she’ll pack the play under one arm. Bembo may or may not take on the guise of musician. ( He did. )

Chiku’s ten calabash were:

-

- the empty: lament, roll call, anatomy, remember

- water : landscape, well gossip, remember

- ugali : kuweri, morning smells, Balima, remember

- milk : legend of the ape princess, Mariam, remember

- millet beer : Lade, song of Jumeni, remember

- salt : sex is very important puppet theatre, to give and to get, messenger’s feast, remember

- intestine soup: census, a soup without salt, Nyasaidi, remember

- blood : Leti’s song, drytime, Myajuma, remember

- duty free : to long for, granny says, the future child, tin roof, remember

- hope : newsletter, roll call, and then, remember

———————————————————–

———————————————————–

THE FUTURE PROTECTION AGENCY /

INSTITUTE FOR NON-TOXIC PROPAGANDA, Bergen 1990.

—

The ‘World Commission on Environment and Development” announced that its European regional “Action for a Common Future” conference, would be held in Bergen. Suddenly journalists and scientists, activists and politicians from thirty-four high-polluting nations were coming to our hometown.

As local artists, we hoped Bergen would supply more than just a pretty backdrop.

DEN MULTINATIONALE SCENE specializes in issue-oriented field-theatre.

We created the FUTURE PROTECTION AGENCY to help receive our guests.

As the unofficial street-theatre of the Bergen Conference, the FPA prepared eight “VISIBILITY PLAYS”.

The INSTITUTE FOR NON-TOXIC PROPAGANDA has since been started to further the application of theatre tools to the imperatives of environmental awareness raising.

Our contribution to the Bergen Conference was a series of street events that provoked both smiles and thought. Poetic and accessible, they were readily lapped up by both print and film journalists. Refreshingly free from diatribe, they allowed well-fed passers-by to speak of their fears without becoming paralysed by feelings of guilt.

Any transition towards an ecologically benign life-style

requires enormous technological and social change. Any desire

to steer this change, will require an equally enormous propaganda effort

However, our over-crowded world of media claim and counterclaim, leaves us little room to move. People know too much. The facts are numbing, and our well ofhope has often run dry. Feelings of helplessness impede our capacity for rational thought. To re-open this connection we turn to the communication techniques of popular theatre.

As theatre workers we possess a specialised knowledge: We subject ourselves to laws of dramaturgy. Laws which decree that new information can’t be presented before the stage has been set and the drama heightened.

A central tool is metaphor . Metaphor frees us from the need to be direct, strictly logical, or diplomatic. Understatement becomes as important as statement. Playwrights can illuminate an argument by ascribing one character an extreme degree of naivete or irrationality. It isn’t always appropriate to underline one’s conclusion.

As the self-declared propaganda arm in an undeclared war, THE MULTINATIONAL SCENE has interpreted our task as awakening collective consciousness. The time is precious. But our work of building imagery that stimulates the fighting spirit cannot be hopped over.

Our INSTITUTE FOR NON-TOXIC PROPAGANDA may be blatantly naive, we shall certainly seek to manipulate. However, our applications of the truth are an honest attempt at propaganda at its best.

Bembo Davies, Bergen 1990

______

Institute for Non-toxic Propaganda :

a division of Den Multinationale Scene, Norway

proudly presents

“VONDT I SPRÅKET”

“PAIN IN THE LANGUAGE”

22 min. short film (1988)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gwNsy8r9y7Y

with:

Chiku Ali,

Ciro Cacace,

Bembo Davies

Helge Jordal,

Brita Moberg

Anthony Rajendram,

Magdalena Sobierajska

camera: Morten Skallerud

sound and editing: Erik Rye

music: Giora Feidman

producer: Tore Severin Netland

written & directed: B. Davies

——

Northern Europe has a long tradition of population export; many people have left, very few have come. This has resulted in a myth of a homogenous people.

The last few years have changed this. A de facto importation has occurred. ‘Different’ population groups have arrived; first as cheap labour, later as economic or political refugees. Suddenly the streets are full of people who look and/or talk funny. These import items have been put into schools, and are steadily encouraged to perform their folkdances. Newspapers are full of debate on the appropriate welcoming ceremony. Despite a new myth of cultural pluralism, the newcomers seldom ‘integrate’ successfully.

Are they so damaged by the process of uprooting themselves ? Do they lack “intergatity” ? In fact, it seems that it is this very integrity, a deeply human dignity that prevents their homogenisation. The act of adults returning to a state of speechlessness is humiliating. When words fail you, people dismiss your thought capacity. At best you negotiate an emotional curfew with society.

The short film “Pain in the Language” is a revenge comedy. With a theatrical lumberjack from Canada at the helm, a group of assorted foreigners found a way of directly describing this syndrome. We do so with a warmth that both testifies to a solidarity between nations and sends surges of jealousy among the homogenous. While Norwegian filmmakers remain morally bound to making ideologically correct reportage about loneliness in the ghetto, we are free to proclaim our ‘broken language’ as a liberation tool: rebellious vowels and misplaced idiom become a new militant poetry.

______

Stimulating Children’s Rites:

“Standing in your Words”

Theatre in Education ‘Mini-project’ at Mount Pleasant School, Southampton

Devised by Frederika Fellman, Gunhild Chifunda, Bembo Davies

If theatre is a ‘rehearsal for reality’, a child’s meeting with fable and fairytale has a similar function. Values and ethics, right and wrong get debated and implanted as vital signposts for future life choices.

If theatre is a ‘rehearsal for reality’, a child’s meeting with fable and fairytale has a similar function. Values and ethics, right and wrong get debated and implanted as vital signposts for future life choices.

So central is this negotiation within the fantastic that substantial areas of our brains seem to be reserved for just this activity. During a child’s formative years, projecting oneself into fictive spheres of existence is a cost-effective survival strategy for gaining real experience. It is often called Play. Many children can’t get enough of it.

Was this inner city school rougher than we could have imagined ?

No not really. Good youngsters with vastly differing needs. The hard-pressed teaching staff was gradually establishing a functional discipline. The constraints of school budgets saw to it that the supply and demand curve further distorted the gender imbalance among the staff. In a world of limited human resources, a daily struggle for sufficient nurturing spawned a competitive cry for attention.

We were aware that drama classes of fifty-five minutes a week for seven weeks would be a passing event in a child’s education. However, it was conceivable that among the many moments of triumph and frustration that comprised their educational process, an event of significant stature could reinforce the essence of what schooling represented in their lives. By elaborating on the ritual elements of assembling our strength in a co-operative endeavour, we could sketch a pattern of collective achievement that might, if only subliminally, stick with a class of nine year olds for a good long time.

——

Literature-based theatre in children’s schooling seems on very stony ground indeed. In a world where one aspires to be Smashman, Marge Simpson, or What’s-his-name Beckham, it may be hard for literature and the naked word to retain any potency at all. Building a conventional, dialogue based play wouldn’t have worked at Mount Pleasant. We chose to interpret the challenges posed by the school board’s fourth year literacy programme literally. The goals were lofty; to stimulate grammatical awareness and vocabulary extension.

Based on two rounds of observation with the students and the application of a basic storytelling exercise in our first class, it quickly seemed that the goals of the curriculum seemed as colossal and gigantic as the approved subject matter – Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man. Despite good pronunciation and a presumed general comprehension, many students were not yet a tempo with age peers from other environments. When navigating beyond the everyday exchange of the classroom, it was not uncommon for the youngster’s active vocabulary to meet realms of unfamiliarity. We found that gaps appeared in their understanding, and that they lacked forms of formality and narrative voice that enabled them to enter into the linguistic qualities of our chosen text. It seemed plausible that some of the shortcomings in the ability to form coherent sentences came when deeper linguistic forms collided with mother tongue syntax. I would speculate that while many students perform satisfactorily, many of the others might be heading for a familiar functional semi-literacy. The curriculum seemed to invite them to begin linguistic gymnastics before they had got their gangly feet under themselves.

After our first active week in the classroom we had articulated our aim as “to stimulate confident and creative use of language through an active theatrical presentation of images from the Iron Man story.” To clarify our work process and give a clear picture of the dominant effort, we chose as our operative project title : ‘Standing in your Words’ This metaphor reflected the desire to help students beyond a threshold or perceived threshold of linguistic competence and towards a reliable eloquence in moments of stress. Our sub-objectives were to stimulate oral skills and voice productive capacity; promote equal participation across gender, classroom status and linguistic confidence, we wished to actively counteract gender programming and increase mastery of expressive tools. A co-incidental division of our project group into one sub group for each class resulted in the three multi-lingual drama students working together; it seemed natural for us to mobilise the youngsters’ multicultural citizenship in exploring the quest for linguistic confidence.

It is appropriate to say that we didn’t meet all of these objectives.

—–

The thrust of theatre is to embody its meaning in its action. To attempt to illustrate the entire story of the Iron Man was never a question. Instead we chose to mine the basic story for its metaphorical wealth. The story was stripped down to its dominant image – a child meets and befriends a creature of great power. Given that Mount Pleasant School boasts eight-meter high ceilings, we elected early on to replicate an ‘Iron Person’ figure in magnificent full size. By getting the students to give the figure the gift of language, we would externalise the objectives of the literacy programme. Our ritual would reinforce this intention by including both verbal and physical elements. We would literally empower our tin can creation by taping words representing our linguistic and cultural richness onto its body parts. That the collective effort of collecting enough tin cans would mobilise the children’s families was considered a plus. Coincidentally their biology curriculum took up the skeletal system, so we consciously strove to reinforce their anatomical knowledge; building both ulnas and metatarsals.

Recognising that there was precious little fiction to get out of this group of untamed charmers, it was quickly obvious that any production would have to occur in reality. The chosen text offered its image : Giant Iron Person. We would have to build it. Initially, I envisaged one giant leg hanging from the flies over the stage; strapping tin cans in muscle shaped plastic bags to a rope wouldn’t take too much effort. Three sketches later, the tins were to be revealed in all their glory. Given such magnificent high ceilings there was no reason not to move out into the auditorium and suspend the whole figure from the rafters. The task of constructing the beastie would be our participatory research; the effort of raising it to the yardarms would be our acting. The triumph of completing a successful project together would be the very real triumph of completing a successful project together.

The mechanical presentation of our collective creation would demand several concrete moments. Tradition decreed that the figure must appear, must collapse, must be brought back to life.1 The children would explore their fear and their capacity to nurture. Filling these actual moments with meaning extrapolated from the Iron Giant story, we inter-twined elements of fiction with the real combination of pride and stage fright that would always be present in the room. If tongue-tied nine-year-olds are to be thrust into the auditorium, it is preferable that they do so as tongue-tied nine-year-olds. Concretely, a rope needed to be pulled twice. The real time act of raising this creation for the first time was to be the true theatre of our work. This conscious engagement of the youngsters both practically and imaginatively we called a ‘Children’s Rites’ approach to theatre. The theatrical ritual we created became giving life power to a giant puppet. Given our seven week time frame, we consciously abandoned the attractive possibility of fabricating forms with the children from scratch; instead we defined our collective creative process as filling our forms with the children’s insights and fantasy.

We felt that several approaches to drama work could enrich the individual connection to the use and love of language. Two central approaches were stimulating the imagination and increasing vocal production. By stimulating their identification both with the story and through individual words, we hoped to engage the young people’s sense of power of their language. We slowly polished verbal and corporal building blocks with which to build our future performance. After two weeks we had four sketchy playing moments in development, after four weeks we counted ten. Our basic work structure was to renew several of the previous week’s elements as a combined warm-up/rehearsal, explore new themes, and leave each session with an indication of next week:

“If the Iron Giant were to come here to Mount Pleasant School today,

are the students here wise enough to be frightened ?”

After the fifth session we adjusted our expectations to conform to reality: we weren’t necessarily far off track, but when questioned admitted requiring the requisite miracle for everything to fall into place. Refusing to panic as the performance date approached, we continued shoving important considerations into the future, content to develop isolated playable elements with which we would later construct the action. Most importantly we had established the perceived emotional centre of the meeting; we had explored the right to fear, various reaction patterns and the sensual realities of the tin cans. Seeing each child bending over the supine figure and whisper their favourite words into the echoy voids of zinc cylinders is a joyous sight. Now to give the figure a backbone and get it on its feet !

The dramaturgical frame of

“Standing in your Words”

COMING OF THE IRON GIANT

Rule of 5 beginnings: Orchestra Bash

Voice opening 1

Wave Circle w words

Sea Sounds

Voice opening 2

Nobody Knows I

Rope pulling

‘In the Darkness’

MEETING THE SCARY: talent show

( Five fears: teeth, knees, hair rising,

voice waving, head squeeze fainting )

Music : Slow backwards walk

First try teeth shake

Bravery Stones

Second try handstand

Bravery Stones

Third try Iron man song X 3

Bravery Stones

Orchestra bash ( with body sounds and head squeeze ?? )

Last try tapping on its leg

Bend

Running scream

BIG LISTENING

Nobody knows II whisper

Body sounds

Text II

Straighten up with Orchestra

Questions

Collapse

BEFRIENDING THE STRANGER

Crawling in with word whispering 2 + 3 + 5 + 3 + 7

Body sounds = shaking up

Helping our Friend

Nurturing songs in many tongues

Arm people ( 4 )

Happy Dance : Iron man song and Nobody knows III

—–

Aziz (not his real name) was often a troubled lad. The endless machinations along the invisible faultlines of the social pecking order among the boys would suddenly leave him helpless with rage. He would shake or run away. At the end of one particularly hard session, with plenty of negative attention and with a concerted effort on his behalf to rein himself in, he suddenly showed his creative side. As we packed up for the day, he held two tin cans to his ears and mimicked his version of the giant figure we had marked out on the floor. It was my turn to shake with glee.

Next week, I chanced to come in contact with him before the class began. I roped him in as co-conspirator; letting him become the first class member to see the day’s key acquisition: this large, light paint thinner tin, scavenged from Precision Welding (the school’s next door neighbour) would become the perfect giant’s head that had eluded us until the last moment. I thanked Aziz for his contribution last week. Consciously elevating the concept of our performance, I told him that ‘I really liked that moment with the ears, would he be willing to put in into ‘the piece’?’ I would have let him impulsively romp across the floor at any point he wished – but when we later needed a key transition for a central moment leading to the piece’s denouement, he willingly took on the task. Several of his friends immediately started vying to inherit this responsibility and had to be shooed off. I anticipated some internal resistance, and when he came by later he expressed concern that people would laugh. I agreed: ‘Most likely, yes. People do have a great need to laugh, so that is very often a good thing.’ He nodded.

Children’s Rites

A roomful of 8 year old children, each clutching an empty tin can between their hands: directed to think about the fact that nearly every one of us in the classroom has a different language at school than we have at home, they lean over and whisper private words into the tins. In a moment they will apply coloured protruding paper tabs to the tins with words from as many languages as they know. Once they are taped on it will look as if the tins have thorns, or wings. Three minutes later they will hammer holes in their tins with a nail, and then string them on lengths of serious gauge wire. Later that afternoon the strings of wire will become the ulnas and femurs of a 5.7-meter high humanoid figure. The bulk of the children won’t meet the figure assembled until the day before the performance; nor will they know their lines…

What they are almost clear about is their relationship to the figure. During our group sessions we have explored fear and its manifestations. We have come forth with small gestures of welcome, but our bravery has ‘turned to stone.’ Before the last rehearsal we had run through the names of the four acts – as actors analysing their script for unit titles we repeat: ‘Coming of the Iron Man’ ( The title of Ted Hughes’ first chapter), Meeting the Scary, Big Listening, Befriending the Stranger. Several of them have grasped the content of our project: They may have created a powerful figure, but they can’t befriend it until they have given it the Gift of Language.

On the day of the final rehearsal we run through the units, refreshing some of our many exercises and seeking to glue them together as an emotionally cohesive whole. Having observed with earlier projects the value of a visible public preparation, this project marked the formal appliance of my ’Law of the Five Beginnings’. Focus and concentration are not automatically in the repertoire of the untrained actor no matter what age. To bridge the gap between being pupils at assembly time and a group of children bent upon resurrecting a potential powerful ally, we introduced an overture of a selection of warm-up rituals. These were to gradually lead the children from general exuberance, to group consciousness, to vocal power, to a reminiscence of how far we have come on the process, to addressing the audience from the safety of the group. No artistic explosive opening; simply ritualised half symbolic actions that allowed time to synchronise our efforts. Aware that asking small children not to make noise with their tin cans is tantamount to torture; we decide to begin the performance by creating a pandemonium of noise and movement; gathering everyone together each with one tin, we warm up our sense of ensemble by everyone banging a can with everyone else. We will repeat this raucous behaviour in each of the four major playing areas among and around the audience.

Creating organic transitions when several mechanical considerations crave their attention is, to put it mildly, perturbing. Half way through the final rehearsal, having achieved a semblance of a progression for the first two segments, the actors are granted a ten-minute run around in the fresh air.

When the ‘actors’ return the giant figure has arisen. They parade in as usual, but suddenly stop up with their necks bent back over. I ask them to remember this feeling of awe. The floor is thrown open: ‘Who has a question for the Iron Giant?’ Well versed in the significance of their ritual meeting they rise to the occasion – relevant and heartfelt. They improvise a mixture of important ideas and recycled clichés from science fiction. When it is established that they are not getting any response – the figure collapses in a clatter. Moving forward they engulf the heap of tins – perhaps an ending will crystallise under tomorrow’s performance. What shall it take to bring it to life ? If we attach these two thin plastic pipes, (also found by the roadside between our train-stop and the school) to the wrists, will at least get the arms to dance.

—–

Tradition dictates ritual. Ritual fills itself with meaning from within the individual.

The final performance may or not be the stuff of legend. The Rite of the Mount Pleasant Iron Giant was performed before the entire upper school – it was loud, it was spontaneous, the ceiling and the ropes held. It wasn’t particularly refined theatre. We had internally assuaged our battered objectives with the thought that ritual exists in infinite time. Tradition dictates that: it has always been such; it will always be such. The mere fact that this was the first time anyone could remember doing such a thing reflected more than anything else, a collective amnesia. Our duty as facilitators was to get all the ingredients to the right place. The assembly of the ritual would be the task of tradition and collective will.

One colleague associated the energy released by our free-flowing romp with medieval peasant festivities of dance and disorder; saying that he half-expected the school’s Headmaster to jump up and douse the resurrected giant with flammable fluid. We hadn’t quite thought that far, although right before winter solstice the piece did cry out for dark and candles. We were probably lucky to that everyone survived in one piece, and can only trust that the legend of the Iron Giant lives on in the memory of the assembled multitudes. What is certain was the immediate gratitude among the students who had triumphantly negotiated a strenuous activity full of uncertainty and potential pitfalls. We felt additionally fortunate that our considered goals were not trampled in the rush to produce.

The explanation for this convergence of good fortune is perhaps of a religious nature. We had adamantly displayed a deep faith in the theatrical process, – the metaphor begat its meaning. Refusing to over-orchestrate the elements into a manageable convenient order, we had negotiated a play – the way children do it.

Winchester

Feb. 2003

1 An excellent traditional model being Mummer’s plays